For decades, neuroscience textbooks taught that the brain rewires itself when a limb is lost. The assumption was simple: when an arm is amputated, the brain’s map of the body reorganizes, allowing neighboring neurons to take over the now-unused territory. But a groundbreaking study published in Nature Neuroscience challenges this long-held belief, showing that the brain’s internal map of the body is far more stable than once thought.

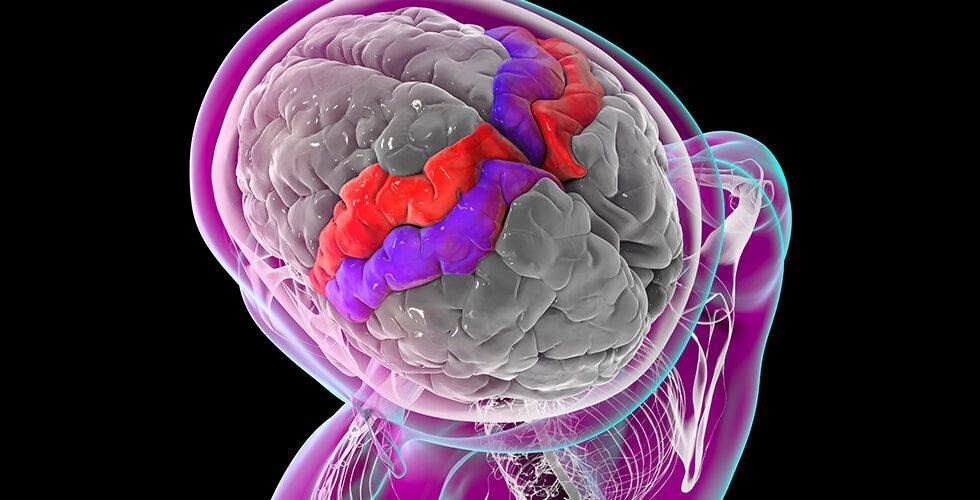

Researchers followed three patients scheduled for arm amputations, mapping their brain activity with fMRI scans before surgery and then for up to five years afterward. During the scans, participants performed movements—such as tapping their fingers or pursing their lips—to reveal how specific regions of the brain lit up. Even when participants moved their “phantom fingers” years later, the same areas of the somatosensory cortex still responded as if the hand were intact.

The results were striking: the brain’s representation of the missing hand didn’t fade or get replaced by nearby regions. In other words, the cortical map endured, seemingly unaffected by the loss of the physical limb.

This discovery overturns decades of assumptions about “cortical plasticity” and explains why many amputees continue to feel vivid phantom sensations or pain. It also offers new hope for developing more effective prosthetic technologies and brain-computer interfaces that tap directly into these stable maps. Instead of trying to retrain the brain, future therapies may work with its natural resilience.

As lead author Tamar Makin of Cambridge put it, “Textbooks can be wrong. We shouldn’t take anything for granted, especially when it comes to the brain.”

The finding doesn’t just rewrite a chapter of neuroscience—it reshapes how we think about memory, sensation, and the remarkable stability of the human mind.